Week 11

Network analysis offers digital humanists the promise of discovering surprising insights into their data that could not necessarily be obtained through other means. This promise has been a recurring theme in the literature that advocates for the various tools that we have studied this semester. My take on network analysis is that it is the tool least likely to fulfill the promise except in very specific circumstances.

Although it is not a factor unique to network analysis, a limiting factor to the potential usefulness of network analysis for digital humanists is the upfront time needed to code the data before it can be analyzed. The coding can be very time consuming, and as has been observed in class, the time spent is not especially recognized as scholarship. A researcher would thus need to think twice about the value of investing time in a technique that might not yield publishable results and might not be acknowledged as worthwhile by peers.

Related to the issue of the time consumed in coding the data upfront is the issue of the work that needs to be done to the resulting network on the backend. As Düring observes, the researcher is likely to notice errors while working with the network visualizations. The researcher then needs to spend time fixing the errors. Time lost while fixing the errors is time that the researcher cannot spend on interpreting the results of the analysis–the most important part of the process.

Another concern that I see with the coding procedure is that it could tend to predetermine the outcome of the analysis. If the researcher assigns similar codes to two separate data points, they will be more likely to be associated in the resulting network. The analysis may then just confirm something the researcher already suspects instead of bringing to light something novel.

Another concern that I see with the error-correction process also originates in the worry that what the researcher already suspects will influence the outcome of the analysis. While correcting errors, the researcher runs the risk of changing errors that are not really errors but instead results that do not fit the researcher’s preconceived ideas of how the network should look.

Along with the researcher’s preconceived notions about the data, another challenge to interpreting the results of a network analysis comes from the complexity of the math that underlies the analysis. Weingart’s cautions about using centrality raise a dilemma in my mind like the one I confronted with topic modeling: do I need an advanced math degree to understand and trust network analysis?

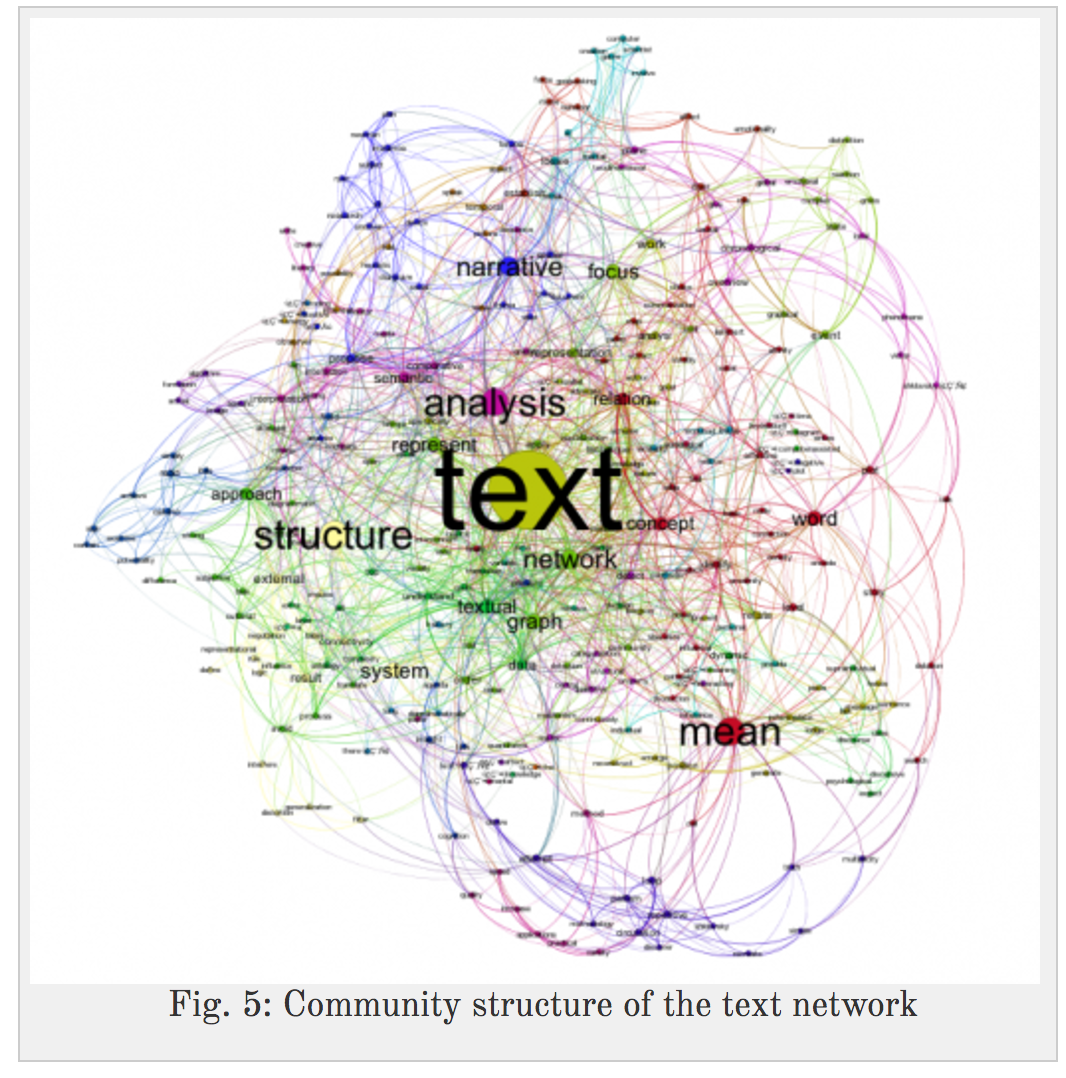

Even if I had the appropriate degree and a thorough grasp of the math, I would not be comfortable assuming that my results would be understood by other humanities scholars. Take the example of the graph from Paranyushkin below.

If I presented readers with a graph like this one, I would feel that I had to provide along with it a lengthy explanation for the benefit of those who are not mathematically inclined. The explanation might fall flat because the readers would not have worked with the data to the extent that I had. The readers might doubt my conclusions because they could not reproduce the process behind the conclusions.

Given the time commitment required to conduct a network analysis and the difficulties related to the presentation of the results, I would not recommend network analysis to, say, English majors looking for insights into literary texts. They would be better off with text mining and topic modeling. The specific humanities application where I see promise for network analysis is, appropriately enough, in analyzing networks. By that I mean doing a project like Düring’s where he needed a tool to help him understand the connections in a historical social network. In the case of an actual network, the visualizations do hold promise for making sense of complexity, and using a different way of reading the material might help a researcher see something that had been overlooked.

Despite my reservations about network analysis, I would still encourage digital humanists to experiment with tools such as Palladio and Gephi as long as they are OK with spending the time and are realistic about the potential results. As Düring says, “The only way for you to find out whether this method makes sense for your research is to start coding your own data and to use your own context knowledge to make sense of your visualizations.”