Week 6

Readings

I found Richard White’s piece helpful for starting to get a handle on what is potentially useful about GIS in humanities scholarship. I particularly appreciated the way in which he described the Spatial History Project as a humble attempt to do history in a different way. I appreciated this because the projects that White and the other authors cover seem to me to be an evolution in scholarship, not some radical new thing that breaks completely with the scholarship that came before. Bodenhamer’s summary of the development of the spatial humanities also presents an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary process.

White states that “our main focus is on visualizations, and by visualizations I mean something more than maps, charts, or pictures.” This illustrates the evolutionary process. Maps, charts, and pictures have long been tools in scholarly work, but as White indicates, the application of computer processing power to these tools has allowed them to incorporate things such as the depiction of movement and changes that happened over time. GIS has the potential to

be what White calls a new means of doing research: “it generates questions that might otherwise go unasked, it reveals historical relations that might otherwise go unnoticed, and it undermines, or substantiates, stories upon which we build our own versions of the past.”

The projects done by Wilkens and by Gregory and Hardie are good examples of work that seeks to undermine or substantiate stories on which we have built our versions of the past. I must admit, however, that I felt some tension as I read the Wilkens and Gregory and Hardie pieces because I was not sure that they revealed historical relationships that might have gone unnoticed. Their results did not strike me as particularly surprising. It seems logical and almost self-evident that fictional texts written in the United States around the time of the Civil War would heavily reference places that featured prominently in the current events of the authors’ lives. Similarly, it makes sense that in the London newspapers of 1653 and 1654, words related to war would cluster around places where battles were taking place.

As I said, the results of the work done by Wilkens and Gregory and Hardie did not surprise me. I was even initially tempted to dismiss the work as unimpressive, but after additional reflection, I concluded that their results have value. The value develops because the authors worked with such large groups of text. The authors used the new tools and techniques to analyze more text than unaided human scholars could process. With that substantial body of evidence to support their conclusions, the authors’ work serves to validate the conclusions in previous scholarship that was built on what people (without the newer technological aids) were able to read and process.

Bodenhamer and Knowles both bring up potential limitations to GIS for scholarship by pointing out that GIS can be too quantitative and lack the human element. Bodenhamer and Knowles suggest similar approaches to overcome the limitations. They talk about GIS projects that incorporate other technologies such as audio and video recording and virtual reality. In these projects, GIS again seems to be an evolutionary rather than revolutionary tool. It is part of the humanities’ ongoing (even if at times reluctant) embrace of the digital.

Examples

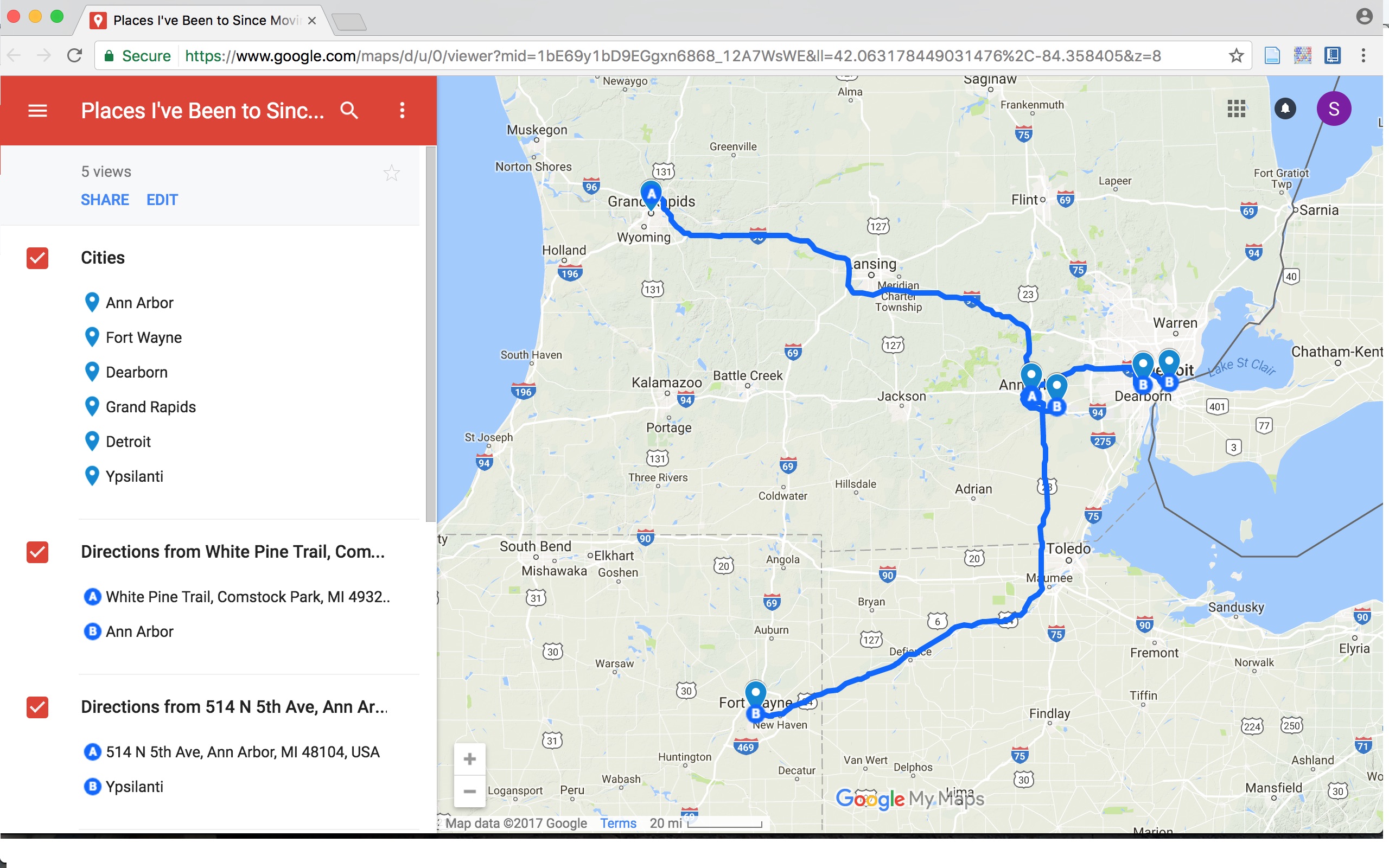

To get a sense of how GIS tools operate, I followed the The Programming Historian tutorial on Google Maps and created a simple map showing places I have been since moving to Ann Arbor as well as driving routes from Ann Arbor to those places.

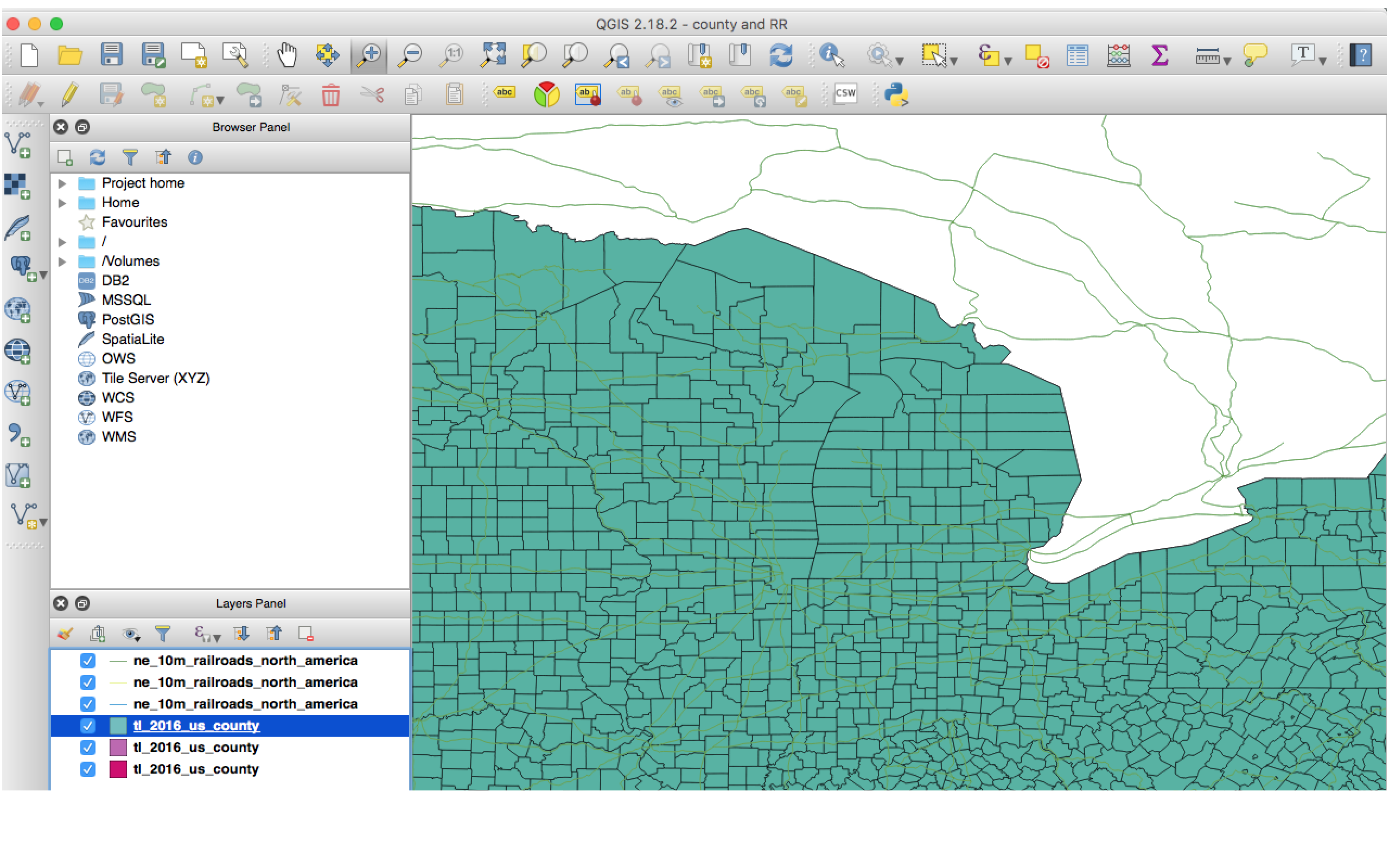

I also used the Making a Map with QGIS tutorial to create the US county map with railroad data.

The GIS tools were straight-forward to use for the tasks outlined in the tutorials; however, I can see that the tools (particularly QGIS) have a steep learning curve for functions that are more sophisticated (and potentially valuable to humanities scholars). The tools thus present a dilemma for scholars: is the time needed to learn the tools worth it for the potential results? Based on the examples of Humanities GIS scholarship that we looked at in class, I hesitate to say “Yes.” The projects had maps that looked good and presented interesting data, but they were often lacking in the interpretation and insight that is expected in humanities scholarship. It is as if the creators left the interpretive work to the users of the maps. This is a further indication of GIS producing an evolution rather than a revolution in scholarship.